“You may not think about politics, but politics thinks about you.” This quote, famously stated by Aung San Suu Kyi, Burmese politician and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, was portrayed by Michelle Yeoh in the 2011 film The Lady.

The Republic of the Union of Myanmar is an independent nation in Southeast Asia with a complex history. It transitioned from centuries of imperial rule under Burmese kings to British colonial annexation in 1886. Myanmar gained independence in 1948, which lasted until 1962, when the country fell under strict military rule. From 1962 to 2011, decades of political oppression and economic mismanagement left Myanmar isolated, impoverished, and subject to international sanctions, making it one of the least-visited nations in the world.

Today, Myanmar is one of the most vibrant and colorful countries in Southeast Asia, drawing increasing numbers of tourists eager to explore its rich history and modern transformation. Beyond its renowned jade, gems, oil, and natural gas, Myanmar has recently entered the specialty coffee scene. The first samples were showcased in 2016 at a cupping event hosted by La Colombe in Philadelphia, in collaboration with Winrok International, Atlas Coffee Importers, USAID, and the Coffee Quality Institute (CQI), represented by Andrew Hetzel.

Before visiting, I knew little about Myanmar beyond its complex political landscape. Since the country began opening up, it has undergone rapid modernization and development, moving from decades of isolation and poverty to becoming more globally connected. Yangon, the former capital, is hot and humid, making it exhausting to explore at times, yet the city captivates with its stunning pagodas and welcoming atmosphere.

My primary goal was to understand Myanmar’s specialty coffee market firsthand—its current state, future potential, and the initiatives being implemented by organizations like Winrok International and USAID to help local farmers improve production, increase income, and elevate coffee quality. After spending two days in Yangon, I took an express bus to Mandalay, the former royal capital in northern Myanmar, enjoying a comfortable nine-hour ride. From Mandalay, I traveled another two hours by taxi to Pyin Oo Lwin, a scenic hill town in the Shan Highlands, known as the heart of Myanmar’s specialty coffee production.

Pyin Oo Lwin is absolutely picturesque, with a cooler climate than Yangon and a peaceful charm influenced by its colonial British history. There, I connected with one of the region’s leading coffee producers, Sithar Coffee. I met with Sithar’s Managing Director, Min Hlaing, who guided me throughout my stay, allowing me to observe every step of coffee production in the area and gain a comprehensive understanding of the work involved on these estates.

So, what is really happening in Myanmar’s coffee industry? According to Winrock International, the USAID-funded Value Chain for Rural Development project seeks to integrate smallholders and rural households into competitive commercial value chains to increase productivity and drive agricultural growth. This five-year initiative, which ran from 2014 to 2019, focuses on improving coffee cultivation, processing, and marketing to attract a broader international audience capable of paying premium prices for specialty coffee. The ultimate goal is to elevate coffee quality—from the farm to the cup—through proper picking, processing, and cupping, ensuring that Myanmar coffee can compete in the global specialty market.

Coffee was first introduced to Myanmar by missionaries in 1885, mostly Robusta. In 1930, Roman Catholic missionaries brought Arabica coffee, which was planted in the southern and northern Shan States as well as in the Pyin Oo Lwin district. According to a 1940 report from the Department of Agriculture of Burma, Myanmar exported 95 tons of coffee between 1932 and 1936. Historically, before the USAID project, Myanmar’s coffee was exported mostly to China and Thailand at very low prices—sometimes not exceeding $2 per kilogram.

My first visit was to Sithar Coffee, a crop-to-cup pioneer in Myanmar, located at an elevation of about 3,500 feet above sea level. The main varietals grown at Sithar are SL34, Catimor, and S795, all achieving Coffee Quality Institute (CQI) cup scores above 83. Sithar is the largest investor in Mandalay Coffee Group, which includes a processing plant and a USAID-sponsored cupping lab serving as an export hub for Myanmar coffee. This facility was developed in collaboration with the local coffee community, and Amy VanNocker from the U.S. currently serves as General Manager under a two-year contract.

Sithar works closely with Winrock, USAID, and CQI, exporting green coffee to Japan, Europe, and more recently, the United States. The company actively promotes women’s groups in Myanmar’s coffee industry and employs state-of-the-art roasting technology from Dietrich. In addition to producing coffee on its 40-acre plantation with 40,000 coffee trees, Sithar purchases beans from smallholder farmers and supplies domestic coffee shops across Myanmar.

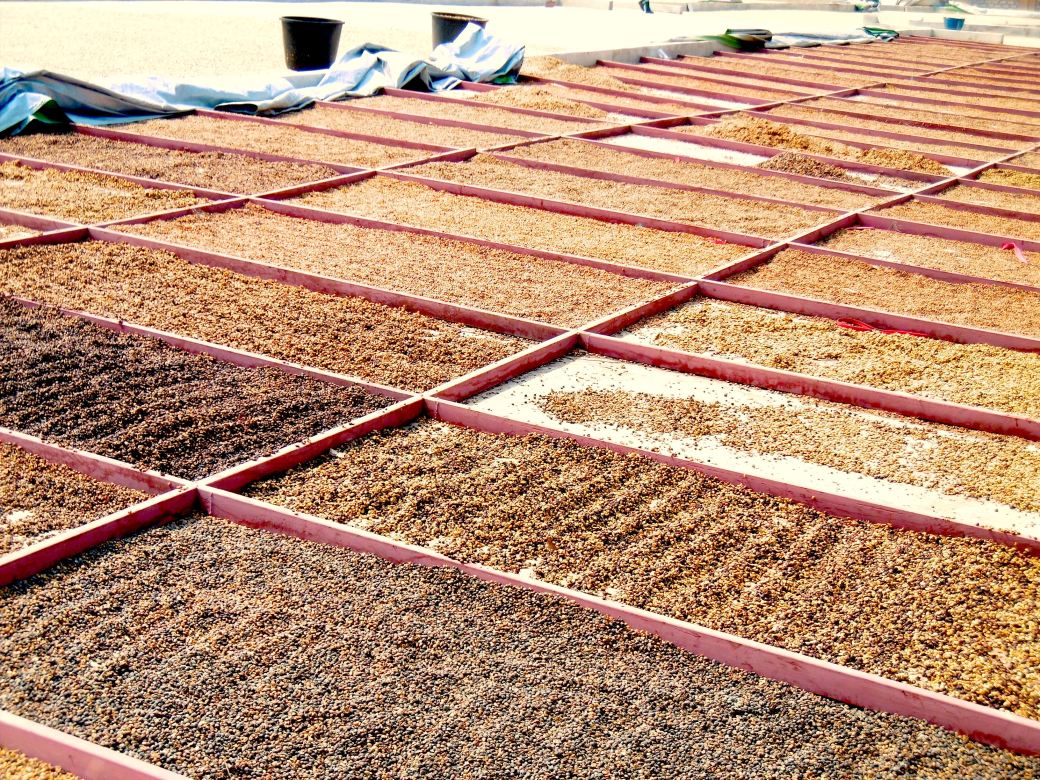

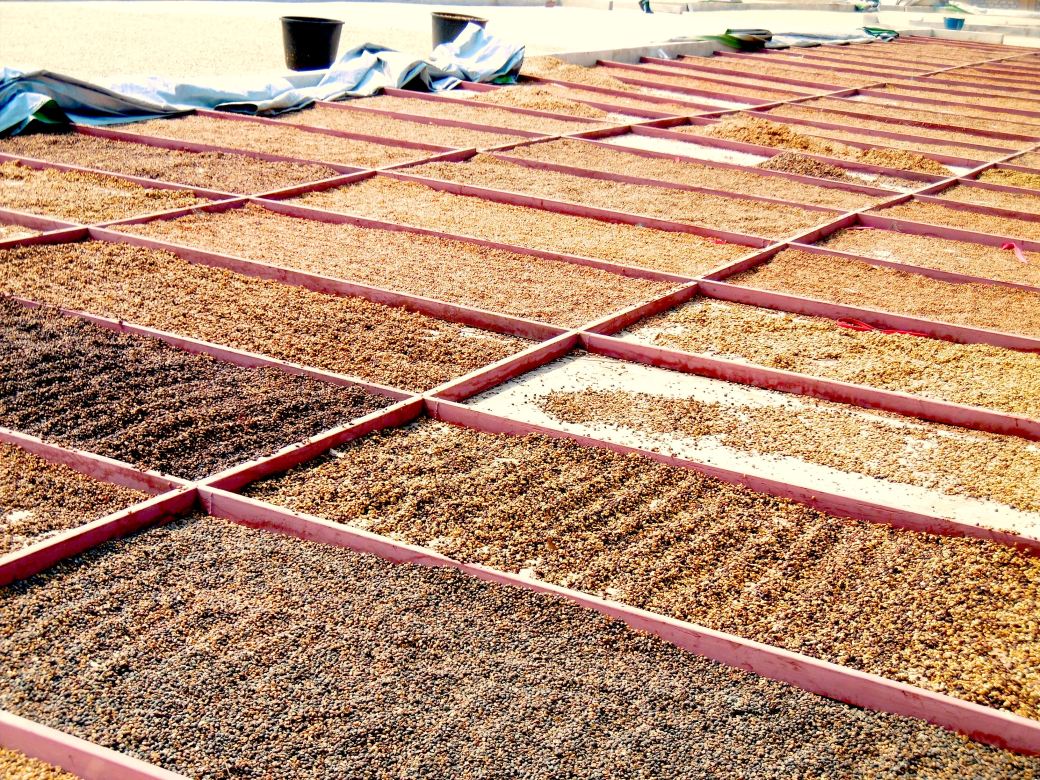

At Sithar, proper cherry picking is paramount. Only ripe cherries are handpicked to preserve the aroma and unique characteristics of the terroir. The farm employs fully washed processing, along with natural and honey processes, to highlight the distinct flavors of each origin. Fermentation is carefully monitored to prevent off-flavors, after which beans are sun-dried to a moisture level of 11–12%.

One of the most fascinating aspects of coffee farming in the Pyin Oo Lwin region is the prevalence of shade-grown coffee. The natural forest surrounding Sithar’s plantation provides shade protection for the coffee trees, which is crucial for proper cherry maturation, ecosystem preservation, and biodiversity. Only bio-fertilizers are used—no chemicals—ensuring the coffee is organically cultivated while supporting environmental sustainability.

The climate of Pyin Oo Lwin is nearly perfect for Arabica coffee, with an average daily temperature of 68°F and annual rainfall of approximately 55 inches. This combination of moderate temperature, high humidity, and fertile soil creates an ideal environment for coffee trees to thrive.

During my visit to the Mandalay Coffee Group, I had the opportunity to cup the winners of this year’s Myanmar cupping competition. I was genuinely surprised to discover that varietals like Catimor and S795—often considered mediocre in the cup—could produce such remarkable flavors. This experience reshaped my perception of certain coffee cultivars, revealing hidden potential in varieties that are often overlooked. It’s clear that the growing environment and choice of varietal have a profound impact on both cup quality and yield. While Myanmar’s overall coffee yield is relatively low, the farms I visited in Pyin Oo Lwin seemed content with their seasonal production, focusing more on quality than quantity.

My next stop was Ngu Shwe Lee Coffee Farm, owned by Kyaw Sein. The farm spans 230 acres, with around 1,300 SL34 varietals planted per acre. Kyaw Sein’s natural process coffee recently placed fourth in a national cupping competition, highlighting the quality of his farm. All coffee trees are grown under shade, promoting slow maturation and allowing the cherries to develop complex flavors.

SL34 is a high-yield cultivar, prized among specialty coffee professionals for its exceptional qualities. Originating in Kenya in 1931 as a mutation between Bourbon and Typica, it was introduced to withstand the heavy rainfall of the highlands while retaining extraordinary flavor characteristics—ranging from fruity and berry notes to bright citrus nuances. According to local sources, SL34 arrived in Myanmar directly from Kenya, while other varietals on the farm were sourced from Brazil and elsewhere. In addition to coffee, Kyaw Sein also cultivates macadamia nuts, diversifying his farm’s production.

Mr. Kyaw Sein employs around 50 people at Ngu Shwe Lee Coffee Farm. Most of the pickers are women, as he explained: “Women have more patience when picking coffee than men, and they are more precise in selecting ripe cherries.” Pickers are paid roughly $0.10 per kilo, while men primarily handle sorting, removing floaters, de-pulping, and drying, earning about $4.00 per day. Gender equality remains an issue on the farm; as Mr. Sein bluntly stated, “women should get paid less than men.”

Like many specialty coffee farmers in Myanmar, those producing high-quality coffee hope for better compensation that reflects the labor-intensive work involved in proper cherry selection and careful processing. Most buyers, however, are unwilling to pay more than $4.00 per kilo for Myanmar coffee. An exception was Atlas Coffee, which last year purchased a container of coffee from multiple farms at $7.00 per kilo—the only time I was told that Myanmar coffee commanded a higher price on the international market.

Recently, Kyaw Sein had a stroke of luck, signing a contract with a Japanese buyer who offered $6.00 per kilo for his natural process coffee, securing one ton of his harvest. It was encouraging to hear, and I sincerely hope he finds more buyers who value the care, labor, and dedication that go into producing quality coffee—not just quantity. Farmers like Kyaw Sein deserve to be rewarded for their hard work, passion, and the love they pour into each bean that ultimately makes our morning cup so enjoyable.

Some of the coffee picked at Ngu Shwe Lee is sent to the Mandalay Coffee Group processing plant for further processing and drying, while other batches—particularly natural and honey process coffees—are processed directly on the farm.

The next stop on my itinerary was Blue Mountain Coffee Farm, also located in Pyin Oo Lwin, Myanmar, at an elevation of 3,632 feet above sea level. The farm is owned by Philie, who earned 4th place this year in the cupping competition for the washed process category. At Blue Mountain, about 25% of the coffee is processed naturally on the estate, while the rest is sent to Mandalay Coffee Group for final processing and post-production.

Interestingly, Philie does not use a moisture meter to measure the moisture content of his beans. Instead, he relies on a traditional technique: biting the bean—if it feels hard, it is ready to be stored in the warehouse for stabilization. The farm spans 75 acres, with roughly 1,200 coffee trees planted per acre. Compared to other farms I visited in the Pyin Oo Lwin region, Blue Mountain focuses solely on the T8667 varietal, a Costa Rican cultivar known for high yields and resistance to leaf rust fungus. T8667, introduced to Myanmar by the government in the late 1980s, is a sub-cultivar of Catimor—developed in 1959 in Portugal as a disease-resistant, high-yield hybrid of Caturra and Hybrido de Timor from East Timor. The plant is relatively short, with large berries and seeds.

It was a pleasure chatting with Philie about the specialty coffee industry and the future of coffee in Myanmar. I shared insights about different processing methods and their impact on the cup profile, encouraging him to experiment with new techniques and provide feedback. All coffee at Blue Mountain is shade-grown, protected from direct sun exposure. Philie also cultivates macadamia nuts, and he shared an intriguing observation: T8667 cherries grown under the shade of macadamia trees tend to be sweeter than those grown under regular trees.

The final stop on my coffee farm journey was Green Land Coffee Plantation. Established in 1999, the farm began with T8667 seeds imported from Costa Rica, while its nursery is largely planted with SL34, the renowned Kenyan varietal. The farm spans 400 acres, with 300 acres dedicated to coffee cultivation, planting roughly 1,200 trees per acre. Green Land earned 2nd place in this year’s cupping competition for the washed process category and also specializes in dry process coffees. The washed process typically lasts 24 to 48 hours.

During harvest season, the farm employs around 150 migrant workers. Most pickers are women, paid approximately $0.10 per kilogram, while men handle processing tasks such as de-pulping and washing, earning about $4 per day. Like the other farms I visited, Green Land practices shade-grown coffee, which protects the trees, enhances bean quality, and promotes environmental sustainability.

The scale of dedication and focus on sustainability and quality within Myanmar’s specialty coffee market is truly remarkable. Every participant in the value chain—from farm to exporter—is driven to gain recognition, earn respect, and command top prices for their work, helping place Myanmar specialty coffee on the global map alongside more established producing nations.

However, some farmers expressed concern about the future once the USAID-sponsored project concludes in 2019. Questions linger about who will monitor production, maintain quality, and oversee marketing efforts. Farmers also hope for better compensation for the intensive labor required to produce high-quality coffee. While they are not unwilling to sell for $4 per kilogram, they want fairer pricing that reflects their dedication and ensures financial stability, allowing them to provide for their families and sustain themselves during the off-season.

The specialty coffee market in Myanmar is still new and developing, but many local coffee shop owners I spoke with noted one consistent point: local consumers generally prefer dark roast over light roast. This preference stems from traditional habits and the cultural etiquette of coffee drinking, rooted in the older generation’s practices. Nevertheless, the specialty coffee scene is steadily moving forward.

I visited Easy Coffee, owned by young entrepreneurs from Singapore, Javier and Melissa Phua. They also run their own roastery, Gentleman Coffee Roasters, and two coffee shops in Yangon. Javier shared that he had previously worked in finance in Singapore and frequently visited Myanmar. Seeking a change from the hectic life in Singapore, he decided to move to Myanmar and start a business—even without prior knowledge of coffee, roasting, or market demand. Initially, the first shop used Illy coffee and tea, but over time, Javier recognized the potential of the specialty coffee market. With the right equipment, careful control of coffee-to-water ratios, extraction, and presentation, he realized that coffee was no longer a commodity—it is an agricultural product whose quality varies with terroir and seasonality, demanding a deeper understanding of flavor.

Thus began the transformation of his shop into a “third wave” specialty coffee venue. Manual pour-over methods, like V60, were introduced, a rarity in Yangon at the time. Unlike other countries where importing coffee can be restricted, Myanmar allows coffee shops to bring in beans from regions like Brazil, Costa Rica, Kenya, and Ethiopia, selling them domestically.

However, an unexpected challenge emerged: finding locally produced Myanmar coffee in Yangon’s specialty coffee shops was difficult. Amy VanNocker from Myanmar Coffee Group explained that high-quality Myanmar coffee is often exported abroad, making it expensive for local shop owners. Consequently, many turned to cheaper imports from other countries, which locals perceived as more exotic, even if the quality was lower.

To address this, Sithar Coffee and Myanmar Coffee Group implemented a plan to retain high-quality Myanmar coffee within the local market, targeting a 50/50 balance for consumption by locals and visitors. According to Javier, demand is now rising steadily. Easy Coffee is located in a quiet, residential neighborhood popular among expats from the UK, US, and Europe, providing a diverse customer base. With support from the Winrock Group, Javier became a certified Q Grader, enabling him to travel north and judge Myanmar’s cupping competitions.

I had the incredible opportunity to taste the 2016 1st place cupping competition winner, brewed by Melissa Phua using a V60. Despite being slightly aged, the coffee showcased remarkable quality: juicy, with delicate acidity, subtle bitterness reminiscent of grapefruit, and dominant plum and cranberry notes. It was a “WOW” moment—an exhilarating first glimpse of the hidden potential of Myanmar coffee.

The next specialty coffee stop on my map was Coffee Circles, located on Dhammazedi Road and owned by two brothers. Zaw-Phone, one of the owners, was in Vietnam judging a barista competition when I arrived, but we eventually scheduled a meeting to discuss the specialty coffee scene in Myanmar.

Compared to Easy Coffee, Coffee Circles does not offer pour-over brewing due to limited demand for black coffee. Their clientele is primarily oriented toward espresso and milk-based beverages. Despite this, the café itself is charming—welcoming, well-decorated, and located in a quieter area of Yangon. The cappuccino I ordered had a perfect velvety finish, with notes of sweet caramel and milk chocolate—a simple yet satisfying cup.

Both brothers are graduates from the US who returned to Myanmar with the vision of introducing and developing the specialty coffee movement in their country. Beyond the café, they operate Element Coffee, located across the street, which distributes coffee grinders, espresso machines, and other coffee-related equipment. Element Coffee also houses a barista school, providing formal training and career development for aspiring baristas, helping elevate the profession in Myanmar beyond a mere job.

Zaw-Phone hopes to see Myanmar coffee gain recognition among specialty coffee communities worldwide, not just as a destination to visit farms or pagodas, but as a place where coffee enthusiasts can broaden their understanding of what Myanmar offers. The Myanmar Barista Championship, first held in 2014 and organized by Coffee Circles and Element Coffee, is a key part of this vision. Although the championship is not affiliated with the World Coffee Events (WCE) due to limited resources and organizational structure, it remains the primary platform where local baristas can compete and eventually represent Myanmar in broader Asian competitions.

Myanmar coffee holds immense potential. Its careful harvest practices, meticulous sorting, and explosive flavors position the country as an emerging specialty coffee region on the global map. I hope the farmers and coffee professionals of Myanmar continue to find strong buyers who recognize the value of their labor and pay fair prices, rewarding the dedication needed to make these coffees truly special rather than commercial commodities.

“The art of people is a true mirror of their mind.” — Aung San Suu Kyi