Have you ever heard of the island nation called São Tomé and Príncipe? Most people have no idea where it is—or even that it exists. That was exactly my reaction while planning my trip across Africa to explore the specialty coffee scene and its rise in the global market. I discovered this tiny nation only when I was looking for a country in Africa where I could obtain an electronic visa rather than going through embassies. São Tomé appeared—seemingly in the middle of nowhere.

Curious, I began researching the country before setting off on the next leg of my coffee adventure after Kenya. That’s how I ended up in São Tomé, eager to uncover its unique environment and discover what this little-known nation had to offer. To reach the islands, I booked a flight with TAP Air Portugal from Accra, Ghana—a short one-and-a-half-hour journey. TAP operates flights to São Tomé from Lisbon, with a stopover in Accra.

The Democratic Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe is a Portuguese-speaking island nation located in the Gulf of Guinea, off the equatorial coast of Central Africa. Despite its small size, it promised a distinctive coffee experience and an opportunity to explore a corner of the world few have visited.

The islands of São Tomé and Príncipe were uninhabited until Portuguese explorers discovered them in the 15th century. Over the course of the 16th century, the Portuguese gradually colonized and settled the islands, which later became a key center for the Atlantic slave trade. Thanks to their rich volcanic soil and location near the Equator, the islands were ideal for sugar cultivation, and later for cash crops such as coffee and cocoa.

São Tomé is not a budget-friendly destination; it tends to be quite expensive. Most visitors are Portuguese or French, though there are also Cuban doctors working in the healthcare sector and occasional tourists from Angola on short holidays. Prices are generally quoted in euros, and ATMs for international credit cards are scarce, so visitors must bring cash. Despite the cost, the islands are very safe to explore on foot, offering a unique opportunity to discover their natural beauty and culture up close.

Now, let’s explore the coffee of São Tomé and Príncipe. The island’s volcanic soil, tropical forests, and equatorial climate combine to create ideal conditions for coffee cultivation. The coffee plant was introduced by Portuguese settlers after their arrival in 1470. At that time, the islands were uninhabited, so enslaved people from Angola and Cape Verde were brought in to work on the plantations.

Initially, the Portuguese brought Arabica seedlings from Brazil. However, Arabica struggled to thrive due to the island’s relatively low elevations, as the species generally requires higher altitudes for optimal yield and quality. In contrast, Robusta coffee, which was eventually planted on the islands, proved well-suited to the local topography and climate. The origins of Robusta here are unclear, but it may have been introduced by enslaved people from Angola or Uganda. Over time, Robusta became the dominant coffee species on the island, adapting successfully to São Tomé and Príncipe’s unique environment.

I decided to explore a coffee plantation in São Tomé and booked a charming lodge in the Monte Café area, about a 20-minute taxi ride from the capital, close to where coffee is cultivated. The lodge was situated roughly 1,000 meters from the actual plantations. The region also features a coffee museum, established with the support of the UNDP in 2008.

While in São Tomé, I learned about Claudio Corallo, an Italian immigrant who studied tropical agriculture at the University of Florence. At age 23, in 1974, he moved to Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) to dedicate himself to coffee and cacao production. There, he managed 1,250 hectares of coffee plantations and provided technical assistance to local governments and small rural producers. Following political turmoil in Zaire, Claudio was forced to leave, leaving behind his land, and later moved first to Bolivia and eventually to São Tomé.

I decided to get in touch with Claudio to have a conversation over a cup of the island’s coffee and discuss the specialty coffee scene in São Tomé. After some email correspondence, I was scheduled to visit his coffee farm, Nova Moca, located southwest of Monte Café, about 5,000 feet above sea level in São Tomé’s coffee-producing region. The farm spans roughly 12 hectares and is absolutely stunning—featuring perfectly cultivated organic soil, a mild climate, and fresh breezes from the Gulf of Guinea, creating ideal conditions for coffee cultivation.

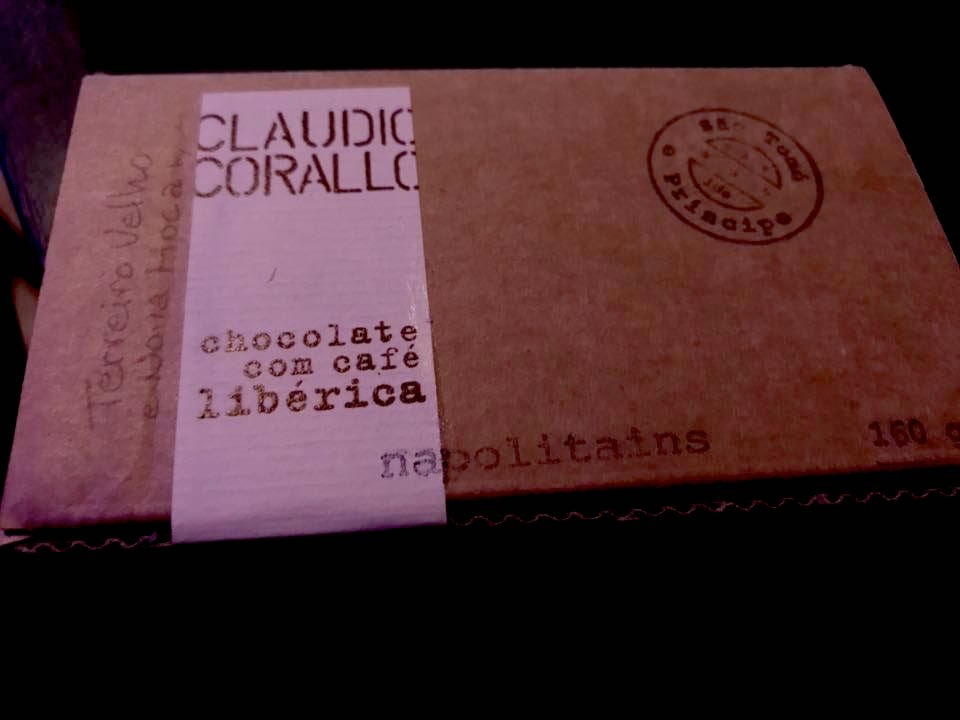

Claudio and his team grow several Arabica varietals alongside Robusta. He also owns land dedicated to the Liberica species, which mostly grows on the island of Príncipe and is primarily used for cacao production. Claudio is renowned for producing some of the island’s finest cacao, and he even operates a chocolate laboratory next to his home. There, he combines Liberica coffee with pure cacao to craft exquisite chocolates. I tried one of his Liberica coffee chocolates and was blown away—it was, without a doubt, the best pure chocolate I have ever tasted.

Liberica is rarely used for coffee consumption or export on the islands because it is less productive than other species. The trees grow very tall, with most cherries concentrated at the top, making harvesting difficult. The beans are also larger and must be peeled by hand, one by one, making the process labor-intensive. Furthermore, its flavor profile—more bitter and less complex—makes it less appealing to the specialty coffee market compared to Arabica or Robusta. Yet, in Claudio’s hands, it finds a remarkable new form in combination with cacao, showcasing the unique potential of this underutilized species.

Claudio employs workers year-round, not just during harvest season, because cacao production requires additional labor for processing and the manual separation of beans. The minimum wage on the island is roughly $100 per month, while coffee pickers earn about $2 per day during the harvest season.

At Nova Moca, the main coffee processing methods are washed and natural. In the washed process, coffee cherries are de-pulped while keeping the mucilage intact. The beans are then placed in water tanks for one to two days to ferment. After fermentation, they are hand-rubbed in running water to remove any remaining mucilage. Once this step is complete, the beans are laid out on African drying beds. Depending on the weather, drying can take anywhere from two to four weeks. Monte Café experiences frequent rainfall—sometimes up to four showers a day—so beans must be carefully monitored and covered during drying.

When the beans reach a moisture content of 10–11%, they are transferred into GrainPro bags for storage. The region’s lush vegetation is maintained by high humidity, persistent cloud cover, and approximately 900 mm of rainfall annually. São Tomé enjoys a hot, tropical, and humid climate year-round, with average temperatures around 30°C from January to April and slightly cooler conditions from June to August.

The next method employed at Nova Moca is the dry, or natural, process. After selecting only ripe cherries to ensure quality, they are laid out on African drying beds. The cherries are rotated constantly—sometimes up to four times a day—to ensure even drying. During rainfall, the beans are carefully covered to prevent water contact. In some cases, after three days on the drying beds, the cherries are transferred to a mechanical dryer to complete the process, reaching a final moisture content of 10–11%.

To avoid over-fermentation or under-fermentation, the natural process at Nova Moca is closely monitored. This intensive oversight preserves the coffee’s inherent flavors while preventing any off-notes or defects, ensuring a clean and balanced cup.

Claudio believes that producing exceptional coffee or cacao requires working in harmony with the environment, nature, and the people who live there. The quality of his products begins on the farm, with meticulous care from seed to cup. Understanding the handling and processing of the beans is essential to appreciating the full potential of the coffee.

Roasting is the final stage, offering a unique insight into the journey of the beans—from harvest to fermentation, drying, and storage—before they reveal the true expression of their terroir. At Nova Moca, the farm is primarily planted with Caturra and Red Bourbon varieties of Arabica, alongside Robusta, each nurtured to achieve the highest quality possible.

After exploring the farm and absorbing as much information as I could, I was scheduled to meet Claudio the following day for a deeper discussion. He welcomed me to his home in São Tomé, where his chocolate factory and laboratory are located, overlooking the ocean in the heart of the capital. He prepared coffee in the traditional Italian style using a moka pot.

Claudio is an extraordinary individual with a clear vision for his products. While our perspectives on specialty coffee differed—he with an old-school approach and I with a modern understanding of specialty coffee in lesser-known regions like São Tomé—our conversation was fascinating. For over 40 years, Claudio has worked to reshape the perception of agricultural products, demonstrating how quality can transform the final product. His dedication has brought significant improvements to coffee and cacao production on the island.

Interestingly, most local people in São Tomé do not drink coffee; it is primarily considered a tourist product for visitors. Coffee on the island is often of poor quality, bitter, and unpleasant to drink, with proper preparation techniques largely unknown to locals. Claudio’s work, however, is changing this narrative, elevating both the quality and the appreciation of São Tomé’s coffee and cacao.

Claudio believes that even Robusta—often overlooked in the specialty coffee market—can offer a pleasant taste and captivating aroma when carefully cultivated and processed. I had the chance to taste his own blend, which combines Arabica (Caturra and Bourbon, washed) with Robusta processed naturally. The coffee had been roasted a month prior and was already ground when I arrived, yet it revealed elegant acidity, a smooth body, and delicate notes of dried fruit—a testament to the unique potential of São Tomé’s coffee. While Claudio did not offer single-origin Arabica varietals, the distinct dry fruit flavors in his blend come primarily from the naturally processed Robusta rather than the Arabica.

Coffee production in São Tomé is limited compared to major coffee-producing countries, which contributes to higher prices. The region’s coffee is valued for its exotic and unique profile rather than the widely celebrated coffees of Kenya or Ethiopia. Export prices for green coffee can reach up to €16 per kilogram, making it less appealing for many specialty roasters. Yet, the exceptional quality of Claudio’s coffee and cacao originates at the plantation. As Claudio puts it, “The quality of coffee begins in the field, just as the quality of wine begins in the vineyard.” Every step, executed with passion and care, ensures that the final product rewards both the producer and the consumer with unparalleled quality.

The magic of true flavor of the coffee from Sao Tome yet to be discovered.

The magic of true flavor of the coffee from Sao Tome yet to be discovered.

Share this:

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Pocket (Opens in new window) Pocket

- Share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

2 thoughts on “The hidden coffee part of the world. São Tomé and Príncipe.”