The Journey Begins at the Farm

The true exploration of coffee begins long before it reaches a roaster’s drum or a barista’s hands. It starts at the farm, with a single seed planted years before the first harvest. What follows is a long, intricate chain of care: patient cultivation, careful harvesting, rigorous sorting, precise processing, attentive drying, proper storage, and safe transportation. Each step demands discipline, dedication, and an unwavering attention to detail.

Only after this laborious journey do the beans arrive to roasters across the world, who unlock the potential shaped by terroir, altitude, and origin. Then, finally, baristas apply their craft—using their tools, training, and intuition to reveal the complex flavors contained within each bean.

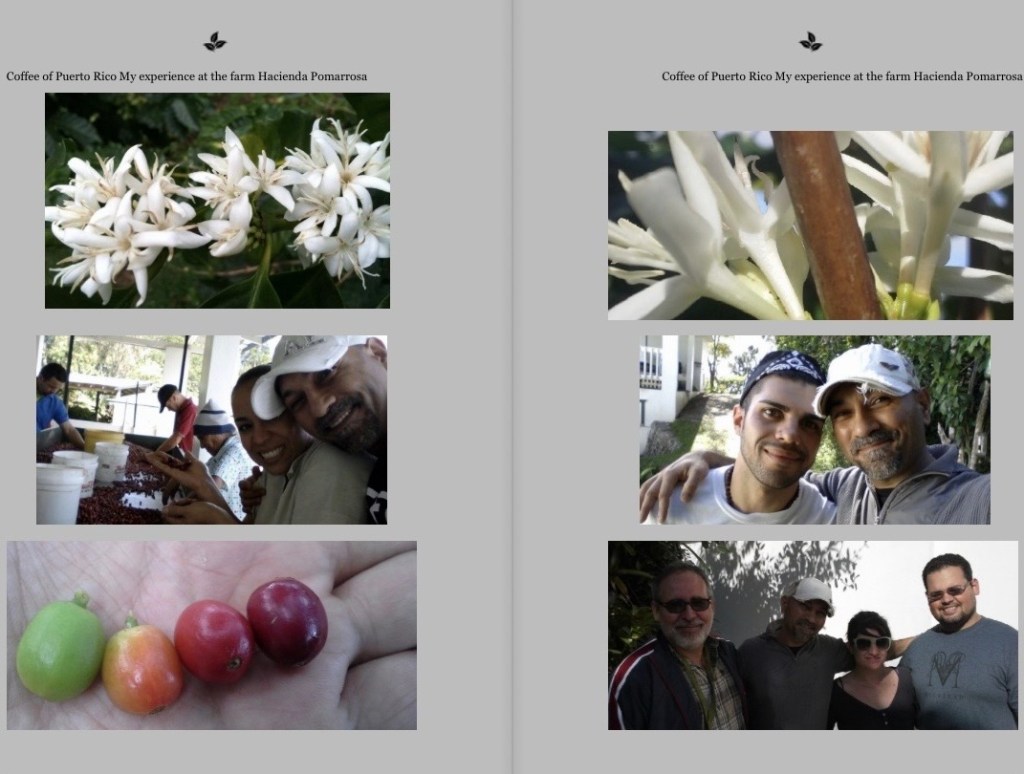

Spending time on a coffee farm reshapes your understanding of the drink entirely. When your own hands pick the cherries, when you feel the weight of the work from soil to drying bed, you gain a profound respect for the producers whose labor makes our craft possible. It deepens your appreciation not only for the bean itself, but for the fragile, extraordinary beverage it becomes. Coffee is, after all, the result of countless unseen hands and immeasurable effort.

A Lifelong Obsession

Coffee is our love, our livelihood, our passion—and sometimes our nemesis. It is a volatile companion: generous and expressive one day, temperamental the next. It demands precision, sensitivity, and humility. If handled carelessly, it will not hesitate to reveal every mistake.

I am a barista, a coffee educator, and a former barista competition judge. My journey into this world began unexpectedly at Tiago Café in Hollywood, California, where I was first captivated by two cups that changed everything: Ethiopian Yirgacheffe and Sidamo. Their explosive florality and vibrant acidity opened a universe of flavor I never knew existed in coffee. In those moments, I realized I had encountered coffee in its most authentic form—the kind our ancestors might have tasted as it traveled from Ethiopia to Yemen, the Ottoman Empire, and eventually to Europe.

From that day forward, my curiosity became obsession. I sought every opportunity to learn, to taste, and to understand coffee more deeply. Each origin revealed a new story, a new character, a new possibility. Coffee became not only my profession, but my calling.

Understanding the Nuance of Specialty Coffee

The specialty coffee sector is still relatively young, yet it continues to expand with remarkable speed. What sets specialty coffee apart from commercial coffee is, above all, quality. In this market, there is no such thing as “bad” coffee. Every origin expresses its own personality—its own character shaped by soil, climate, altitude, and tradition. Preferences among coffee drinkers have less to do with the bean and more to do with the palate. A preference for the creamy, buttery notes of Papua New Guinea over the wine-like acidity of a Kenyan coffee does not imply that one is superior to the other, nor does it suggest an underdeveloped sense of taste.

What truly disqualifies a coffee from entering the specialty world is not the origin, but poor processing or inadequate sorting. The bean itself is rarely the culprit.

As a taster, I approach every coffee with curiosity, always hoping to discover what makes it uniquely itself. My ritual begins with inhaling the dry fragrance, then the wet aroma as the grounds bloom. I allow the cup to cool for several minutes—often up to ten—before taking my first sip. This quiet moment is essential. It lets me form a personal dialogue with the coffee, to understand its character, identify its surprises, and mentally narrate what I enjoy and what I resist.

Coffee, to me, is like reading a romantic novella—each cup a new chapter, each origin a different storyline.

My favorite origins are Ethiopia and Kenya, followed by Rwanda, Tanzania, and Burundi. I gravitate toward filter coffees with layered aromatics that carry through to the cup—juicy acidity, silky mouthfeel, vibrant fruit and berry notes, floral highlights, sparkling sweetness, and a clean, elegant finish. For espresso, I seek a different profile: creamy, nutty, chocolatey, yet still lifted by subtle florals.

Falling in Love with Coffee at the Source

My fascination with coffee production and agriculture began during my early years as a barista in Los Angeles. Yet it wasn’t until I became an intern with Big Island Coffee Roasters in Hawai‘i that this interest truly took shape. In January 2014, I worked on a coffee farm for the first time. That experience reshaped everything I thought I knew about coffee—deepening my respect for producers and intensifying my own passion for the craft. It was there, among the trees and drying beds, that I fell in love with coffee all over again.

Pursuing Knowledge Through Coffee

I have always believed in beginning again—returning to the starting line, exploring something new, and embracing the humility required to learn. I never claim to know everything; in fact, the more I learn, the more I realize how little I truly understand. Coffee has taught me that. It is, and will always remain, a continuous education. Much like life, family, or relationships, there is no final graduation. No matter how many schools you attend or years you spend studying, your real education unfolds along the path you walk each day.

My personal motto is simple: take everything you can from this life, because one day you will look back and realize the game is over.

A New Chapter: Puerto Rico

After my internship in Hawai‘i ignited a deeper interest in coffee production, I wanted to take my learning further. That desire led me to Puerto Rico—one of only two coffee-producing regions within the United States. The idea first surfaced in June 2014, and after corresponding with Hacienda Pomarrosa, I booked a flight for October.

While working at a café in Santa Monica, we had received several coffees from Hacienda Pomarrosa to feature in our shop. Yet the coffees struggled on the cupping table and in brewing: they lacked sweetness, offered little brightness, and finished too dry. At $17 for half a pound, the coffee did not justify its price. Something seemed lost in translation, and I felt compelled to understand why.

At the same time, life in Los Angeles had become overwhelming—long hours, relentless stress, and a sense that I needed a new direction. So I packed my suitcase, left my apartment and job behind, and flew to Puerto Rico with the intention of learning, experimenting, and contributing in whatever way I could.

Hacienda Pomarrosa: Beauty and Challenge

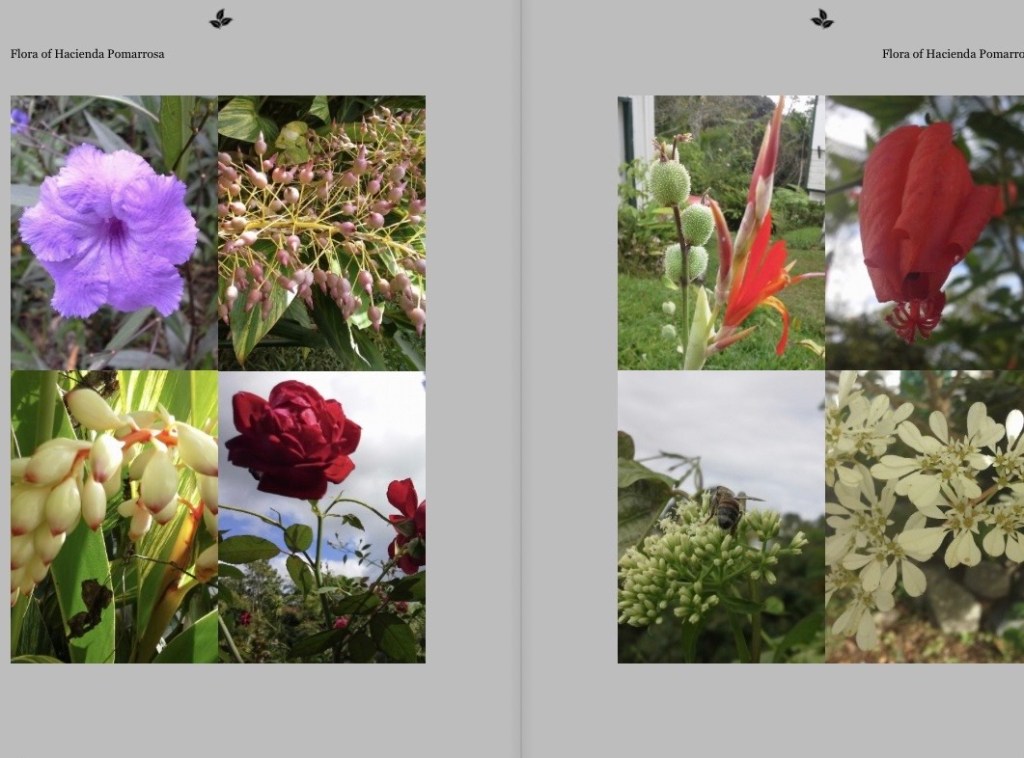

Hacienda Pomarrosa is one of the most picturesque farms in Puerto Rico. Some call it the “Disneyland of coffee,” others see it as a tourist attraction—but beneath its charm lies a working farm in need of renewed attention. Nestled at 3,000 feet, the farm receives cooling breezes from the Caribbean Sea but suffers from limited sunlight and near-constant cloud cover. Frequent rainfall and cool, moisture-laden air place the farm in a unique microclimate that straddles tropical and wet climate zones.

This complex environment—shaped by latitude, elevation, vegetation, and proximity to the ocean—influences every aspect of the bean’s development. My experiments aimed to analyze and enhance the farm’s flavor profile by considering all these factors: variety, soil composition, shade-grown conditions, and the surrounding flora, including citrus trees, bananas, rose apples, and tall pines that shelter the coffee shrubs.

The coffees I tasted at Pomarrosa showed promise: good body and early notes of stone fruit. Yet the flavors rarely carried through the cup, sweetness was lacking, and the finish remained persistently dry. These were issues worth addressing—and my work there became the first step in understanding how to elevate the potential of Puerto Rican coffee at its source.

Reassessing Puerto Rico’s Coffee Reputation

For years, I had heard mixed—and often unflattering—opinions about Puerto Rican coffee. Many described it as earthy, muted, or lacking refinement. Yet these critiques rarely reflected the potential of the land or the varieties grown there. The real issue lay in inconsistent processing practices.

On farms like Hacienda Pomarrosa, pickers often combined cherries of varying ripeness, while hybrids or mutant varieties were mixed with traditional cultivars such as Caturra, Typica, and Sarchimor. The result was inevitable: uneven, disappointing cups that failed to reflect the coffee’s true potential. Consider this: two coffees from the same variety, grown in the same region, harvested on the same day—blindfolded, one might seem unremarkable while the other shines. The difference lies in the quality of the harvested cherries.

Unripe cherries yield bitterness.

Overripe cherries can introduce vinegary, fermented, or even rotten notes.

Perfectly ripe cherries, however, are vibrant, sweet, and full of potential.

Clean, disciplined processing is the backbone of specialty coffee—and one of Puerto Rico’s greatest challenges. Poor technique can introduce flavors reminiscent of onion, manure, or other off-notes, while inadequate storage can leave coffee tasting flat, dull, or like burlap.

A Developing Coffee Culture

Many of Puerto Rico’s roasters are also farmers. Some possess deep experience; others are driven by curiosity. In cafés across the island, I often encountered overly dark, oily roasts, usually employed to mask flaws from inconsistent processing. The specialty coffee scene here is still emerging. The foundation is present, but achieving consistency demands dedication, risk-taking, and a willingness to evolve.

Understanding the Challenges at Origin

When I moved temporarily to Puerto Rico, my goal was full immersion—to understand farming, processing, and climate influences firsthand. At Hacienda Pomarrosa, two persistent threats quickly became apparent: the coffee berry borer and leaf rust. The berry borer burrows deep into the coffee cherry, damaging beans and reducing cup quality if left unchecked. Leaf rust, a devastating fungal disease, spreads via airborne spores, particularly during rainy periods. Once it infiltrates the leaves, it erupts into rust-colored lesions, weakening or killing plants. Without proper management, entire farms can be decimated.

The Potential of Puerto Rican Coffee

Despite these challenges, Puerto Rican coffee can deliver compelling flavor when handled with care. Many cups exhibit mild acidity, delicate sweetness, and dried fruit notes, especially prune, complemented by subtle pine and cedar nuances. These coffees perform well as single-origin espresso or as part of blends, where pairing with East African beans can elevate complexity and body. For Puerto Rico to fully compete in the specialty coffee market, the island must continue to refine its practices, invest in education, and embrace consistency. The potential is unmistakable; the challenge is unlocking it.

Breaking New Ground in Puerto Rican Coffee Processing

Most coffee farms in Puerto Rico rely on the washed process. However, growers at lower elevations—typically between 1,500 and 2,000 feet above sea level—often choose pulp-natural or natural processing, especially in areas where rain is less frequent. At Hacienda Pomarrosa, I began my work by attempting a natural process, but the island’s persistent rainfall made it nearly impossible. Without raised, covered drying beds and relying instead on a mechanical dryer, the natural process quickly became unmanageable, and I was forced to abandon it.

My experiments were ambitious—nothing like them had been attempted on the island. I planned to introduce processing techniques inspired by washed Ethiopian and Burundi natural process. But proper harvesting and processing had been long overlooked on the farm, and my approach was not immediately welcomed. The resistance made the project far more challenging than anticipated.

Learning by Doing—Alone

At the beginning, I worked entirely on my own. My days started at 6 a.m. with a simple breakfast of oatmeal, raisins, bananas, and a cappuccino before heading straight into the fields to pick cherries. My focus was on selecting only the ripe, red Typica and Caturra cherries, but the varietals were planted irregularly across the steep terrain rather than in organized rows. Unlike my experience in Hawai‘i—where the land was flatter and harvesting far easier—Hacienda Pomarrosa’s mountainside location made the work physically taxing, especially in the rain. The slopes became slick, and more than once I slipped and spilled a full bucket of cherries. Each time, I picked up every cherry by hand rather than leave them on the ground.

The first day left my arms covered in insect bites—ants, bees, and other small creatures that called the farm home. I stepped on anthills, got stung, and still carried on. Picking ripe cherries demands immense patience; it took nearly four hours to fill a single 36-pound bucket, and another four to five hours to fill the next. With these buckets, I began the experimental processes that would define my time at the farm.

The Limitations of Traditional Processing

Hacienda Pomarrosa, like many farms on the island, relied on a conventional washed process: cherries were sorted to remove debris, run through a mechanical depulper, soaked in water for 12 hours, and dried in a mechanical dryer. But this system had significant limitations.

The dryer lacked sufficient capacity to handle the volume of cherries harvested five days a week. When it overflowed—as it often did—the depulped beans were left soaking far longer than intended, leading to inconsistent fermentation. Once transferred to the dryer, the beans were not rotated during drying, creating moisture disparities: one side might read 10% moisture while the opposite side lingered at 8%.

These inconsistencies compromised cup quality. Under-dried beans risked mold or even fungal development, while over-dried beans lost sweetness and complexity. Worse still, improperly dried lots were routinely mixed with properly dried ones, making uniformity impossible.

Clean, precise, and efficient drying is one of the most critical defenses against quality loss. At Hacienda Pomarrosa, the lack of such controls was a major obstacle—and a central challenge I aimed to address through my experiments.

Moisture, Storage, and the Battle for Quality

As the International Trade Centre notes, “When moisture drops below 10%, aroma, acidity, and freshness begin to fade away, and at 8% or below they have completely disappeared. For this reason the ICO prohibits shipments of coffee below 8% moisture content.” This standard exists for good reason. Coffee that dries too far loses not only its vibrancy, but also its structural integrity.

At Hacienda Pomarrosa, the storage conditions posed an additional challenge. Although the warehouse kept the coffee dry, it did not maintain a cool environment—allowing the beans to continue drying long after processing was complete. When I evaluated the previous year’s crop, I saw clear signs of overdrying: an abundance of shells and broken beans, which are more prone to fracturing during milling. These defects inevitably reduce both quality and market value.

Working Alone—and Working Against the Odds

The first two months on the farm were especially demanding. The farmers offered no assistance, leaving me responsible for every stage of the workflow: picking, sorting, depulping, and processing. To ensure consistency, I adapted my methods with precision. I soaked cherries to remove floaters—defective or underdeveloped beans, often affected by pests like the coffee berry borer—before depulping them manually to retain as much mucilage as possible. Then I soaked the mucilage-covered beans again to eliminate remaining floaters before beginning my controlled fermentation experiments.

Every detail mattered. I monitored fermentation carefully to avoid overprocessing and tried to maintain strict uniformity across each lot. My goal was ambitious: to produce at least 80 pounds of coffee from each processing method—washed, honey, and natural—to meet the standards of specialty coffee. But completing all this work alone, under difficult environmental and logistical conditions, proved far more challenging than I ever imagined.

The Price of Premium – Inside Hacienda Pomarrosa

Hacienda Pomarrosa is a high-profile farm, known for its expensive green and roasted coffee: $25 per pound for green beans and $17 for a half-pound bag of roasted coffee. Yet, despite these premium prices, the quality was constantly at risk. Improper picking, inconsistent washing, and inadequate drying undermined the beans’ potential.

Quality control at the farm was minimal. The only sorting was done by a woman named Modesta, who visited twice a week to remove quakers—underdeveloped beans revealed after roasting. This approach alone explained why the coffee often underperformed. I spent hours removing defects from the green beans myself before roasting, but Hacienda was unwilling to hire additional help or invest in machinery to grade and sort beans before roasting. Their reluctance made the process a constant challenge, but it also gave me invaluable insight into the effort required to produce high-quality coffee. Our many debates about improving standards often felt like talking to a brick wall.

What I was attempting at Hacienda Pomarrosa was unfamiliar to the farm. I aimed to shift their perspective, raise quality, and introduce more rigorous standards. A key issue was harvesting: selective picking—choosing only ripe cherries or separating varietals such as Typica and Caturra—was not practiced. Selective harvest is labor-intensive and requires proper training and higher compensation for pickers. In Puerto Rico, minimum wage laws apply, unlike in much of Central America or East Africa, where labor is cheaper. This reality makes coffee production on the island—and in Hawaii—significantly more expensive.

If Puerto Rico were an independent nation with its own currency, labor costs might be lower, and international investment more likely. Direct-trade relationships with specialty roasters willing to pay for quality could transform the industry. Until then, farmers face structural limitations that constrain the potential of their coffee.

After six weeks of picking, sorting, and processing alone, I finally convinced the farm to provide support at the sorting table. I requested two additional sorters to help separate red, ripe cherries from the daily harvest and process them according to my method. Jessica and Maria became my saviors. With their help, tasks that once consumed entire days could now be completed in two to three hours, filling multiple baskets of carefully selected cherries—an essential step toward achieving specialty-quality coffee.

Harvesting Challenges and the Quest for Puerto Rican Coffee Excellence

At Hacienda Pomarrosa, the standard approach to picking was simple but far from ideal. Pickers were paid minimal wages and instructed to strip entire branches of cherries—green, yellow, or red—without discrimination. Any deviation from this method risked losing the pickers, who could easily move to another farm. Many of the workers living in the mountains relied on government welfare, treating harvesting as a supplemental way to earn extra cash. Their schedule was strict: start at six in the morning and finish by noon. I tried to offer a new perspective on quality, emphasizing selective picking and attention to detail, but the results were limited.

Puerto Rican coffee has long struggled to earn recognition in the specialty coffee market. The challenges are manifold: convincing workers to harvest only ripe cherries, carefully monitoring processing methods, and applying meticulous post-hulling sorting to clean, grade, and pack the beans. I took it upon myself to supervise every step, aiming to elevate Puerto Rican coffee to its full potential and reveal the unique flavors this island could offer.

My first experiment began on October 17, 2014, using the Ethiopia washed process. I harvested 65 pounds of coffee by hand, a task that took from 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Care was essential—cherries on each tree ripened at different times, requiring constant attention to the branches, high and low, and deep into the foliage.

Many in the specialty coffee world had dismissed Puerto Rican coffees as dull, earthy, or unremarkable. The blame lay not in the beans themselves, but in the methods of production, which failed to meet specialty standards. From my first day on the farm, I began removing defects from the green beans of the previous year’s crop. When I finally brewed the coffee using a Chemex, the results were revelatory.

Cupping is useful for assessing body and acidity, but it rarely reveals the full spectrum of flavors; sometimes it even masks the coffee’s true character. Brewing, by contrast, transforms perception, unlocking the complexity hidden within the beans. That first cup was a revelation: medium-bodied with a velvety texture, warm and inviting, yet layered and challenging, inviting every sense to uncover its nuances. The acidity was mild, with notes of prunes, milk chocolate, and dark raisins. As the coffee cooled, subtle pine notes emerged, reflecting the unique terroir of Hacienda Pomarrosa.

This experience reshaped my understanding of what was possible in Puerto Rican coffee. Despite challenges with labor and traditional practices, it became clear that with care, attention, and experimentation, the island could produce coffee that was not only attractive but genuinely compelling—rich in complexity, distinct in flavor, and worthy of specialty recognition.

Elevating Puerto Rican Coffee – From Harvest to Global Recognition

My goal at Hacienda Pomarrosa was ambitious: to elevate Puerto Rican coffee to a level of quality that would earn respect and recognition worldwide. On October 18, 2014, nine university students joined us as part of an educational program to help with the harvest. I instructed them to focus exclusively on red, ripe cherries, and the results were remarkable. We achieved a 98% selection of exceptional cherries, which I personally soaked to remove the floaters—beans that did not sink, often indicating defects.

Yet, I quickly learned that this method was not foolproof. Some green cherries and partially ripe berries sank as well, so manual sorting was necessary to ensure consistency and achieve the highest quality. Every step, from harvest to sorting, became a meticulous exercise in precision and attention to detail.

The next phase was to prepare Hacienda Pomarrosa’s coffee for evaluation by specialty professionals in the U.S. and Europe. The previous year’s crops had failed to impress due to poor processing and inconsistent sorting. Feedback was blunt: the coffee lacked sweetness, acidity, and brightness, leaving a dry, flat aftertaste. I made a promise—to transform the processing methods and demonstrate that Puerto Rican coffee could surprise even the most discerning palates.

However, raising quality was only part of the challenge. The local market presented its own limitations. Specialty coffee shops in Puerto Rico struggled to increase prices. While coffee consumption is high, most consumers were unwilling to pay more than $1 for an espresso, $2 for a cappuccino, or $2–$3 for a filter coffee. Many local palates had never tasted coffee beyond Puerto Rican beans, making it difficult to appreciate subtle flavor profiles compared to Ethiopian or Kenyan coffee.

Compounding the challenge was corporate influence: Coca-Cola dominates the Puerto Rican coffee market, blending low-quality imported beans from Guatemala, Mexico, and other Central American regions with local coffee, and selling the resulting product cheaply. This makes it nearly impossible for small specialty roasters to compete on price.

Despite these hurdles, I firmly believe in the potential of Puerto Rican coffee. With the dedication of local farmers who understand the specialty market, the island can offer not only its renowned beaches and vibrant culture but also a coffee that is truly world-class. Achieving this requires patience, precision, and a willingness to invest in quality at every stage—from selective harvesting to careful processing and thoughtful roasting.

Puerto Rican coffee, when done right, can compete globally, delighting the most sophisticated palates and proving that this island’s potential goes far beyond its scenic landscapes.

Exploring Sarchimor and the Legacy of Hacienda Pomarrosa

Like many farms in Puerto Rico, Hacienda Pomarrosa grows more than the traditional Typica and Caturra varieties; it also cultivates Limani, commonly known as Sarchimor. This hybrid, a cross between Villa Sarchi and the Timor hybrid, is notable for its thick trunk, short lateral branch internodes, and large, dark green leaves—new leaves sometimes emerging green or tan. The cherries are generous in size, ripening to a vibrant red, and production performance is comparable to Caturra. While Sarchimor is resistant to coffee leaf rust, it remains vulnerable to the berry borer.

I had the opportunity to taste Sarchimor, and while it was not extraordinary or highly complex, it offered something distinct. In my view, Sarchimor works best as an espresso with a more saddle-like profile, offering mild acidity and a robust body. For pour-over, it can be enjoyable on its own for those seeking simplicity, but blending it with more complex coffees, such as East African or select Guatemalan varieties, can enhance diversity and depth in the cup.

One of the Sarchimor coffees I tried came from the Lucero Farm, owned by Lucemy Velasquez, and roasted by local Q-grader Alfredo Rodriguez. The resulting cup delivered a full body, semi-dry texture, and pronounced aged oak notes, finishing with a slightly harsh, woody aftertaste.

Hacienda Pomarrosa is relatively small, spanning roughly 8 acres—6 dedicated to coffee and 2 to property—with about 8,000 coffee trees. In a good year, the farm produces approximately 6,000 pounds of cherries, but climate variability has impacted yields significantly. In 2014, leaf rust, or la roya, reduced the harvest to just 2,000 pounds.

Beyond coffee cultivation, the farm supports tourism through three small houses rented as bed-and-breakfast accommodations and coffee tours, complementing its growing and processing operations. When German immigrant Kurt Legner purchased the property 22 years ago, it was largely wild grass and trees. The first coffee trees were planted by Kurt and his son, Sebastian.

Hacienda Pomarrosa’s trees are shade-grown, creating a bird-friendly environment that enhances biodiversity. Shade-grown coffee tends to yield less but produces higher-quality beans. Unlike sun-grown coffee, which relies heavily on pesticides, fertilizers, and herbicides, shade-grown coffee benefits from natural nutrients provided by decomposing leaves. Birds, in turn, help control insects, and the farm’s soil ecosystem—teeming with plant roots, worms, bacteria, and organic material—releases essential nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, which are absorbed by the coffee trees’ roots.

The care taken at Hacienda Pomarrosa, from varietal selection to ecological stewardship, illustrates the potential for Puerto Rican coffee to produce unique, high-quality cups while maintaining environmental balance.

Sun, Soil, and Sustainability – Coffee Production at Hacienda Pomarrosa

Sun-grown coffee rapidly depletes soil moisture, causing faster deterioration and forcing coffee trees to grow and age more quickly. In contrast, altitude plays a critical role in the quality of Arabica coffee: higher elevations typically yield beans with greater sweetness and brighter acidity. However, producing exceptional coffee on an island presents unique challenges. In Puerto Rico, the highest coffee-growing elevation reaches only 3,000 feet above sea level. This does not mean that sweetness or acidity is absent; properly processed, carefully selected ripe cherries can still achieve remarkable flavor.

At Hacienda Pomarrosa, coffee trees are planted at one year old. The first harvest typically begins after three years, and by the fifth or sixth year, yields begin to decline, requiring careful pruning to restart the growth cycle. The harvest season in Puerto Rico generally spans from October to January. Pickers must revisit the same trees multiple times, as cherries do not ripen uniformly. In 2014, the harvest began unusually early, in September, and concluded by late November due to widespread leaf rust (la roya). Early completion allowed the farm to prepare for immediate treatment with copper sulfate solutions, targeting any affected trees to prevent the fungus from spreading and decimating the crop.

The processing machinery at Hacienda Pomarrosa includes a sorting table where 6 to 8 women remove debris and unripe cherries. Unfortunately, the green cherries are often sold to government receiving stations without quality control, undermining any potential for specialty-grade coffee. In Puerto Rico, cherry weight is measured in almud, roughly 28 pounds per unit, with pickers earning $8.50 per almud. It takes approximately 7 pounds of cherries to produce a single pound of roasted coffee.

Once sorted, cherries are manually pushed into a water channel leading to a mechanical de-pulper, which removes the skin and, through friction, much of the mucilage. Green beans are then transferred to a drying room, often soaking overnight. Due to limited dryer capacity, beans frequently over-soak, resulting in over-fermentation and negatively affecting cup quality. Drying occurs in a mechanical silo with indirect flame for 24 to 36 hours. After drying, beans remain in parchment before being hulled through a vibrating machine that separates by size and removes remaining skin and mucilage.

Waste from the pulping process is collected in a fermentation tank for about a year, then dried for six months before being repurposed as natural fertilizer—a full-circle approach where the farm returns nutrients back to the trees.

On October 14, 2014, I, along with other Puerto Rican baristas, visited Hacienda San Pedro for coffee picking and to meet Italian barista Angelo Segoni, who was preparing for the 2015 Italian Barista Competition. The night harvest at Hacienda San Pedro was deliberate, designed to study sugar content in cherry pulp at night versus daytime—a practice already explored by innovative farmers such as Graciano Cruz and Joseph Brodsky.

Puerto Rican coffee, like the island itself, requires ingenuity, patience, and adaptation. Every aspect—from sun, soil, and shade to fermentation and processing—directly influences the cup. Understanding these complexities is essential for elevating the quality of coffee from local farms like Hacienda Pomarrosa to a standard respected on the global specialty market.

Refining the Process – From Cherry to Cup at Hacienda Pomarrosa

In coffee production, timing can be everything. The sugar content of the cherry often peaks during the night or early morning, when the sun is down and the air is cool. Recognizing this, one of the most important pieces of advice I shared with Sebastian was to remove defects from green beans before roasting. Once beans are roasted, identifying and separating those damaged by berry borer or other insects becomes exponentially more difficult.

Storage was another critical area for improvement. After drying, beans must be kept in a cool, shaded environment, as exposure to heat and humidity causes them to reabsorb moisture, compromising quality. Hacienda Pomarrosa maintains a strong relationship with Boot Coffee in California, sending periodic shipments for evaluation. Discussions often arose about the optimal resting period for green coffee in parchment before hulling. Boot Coffee recommended a full year, while Stumptown Coffee Roasters suggested 60–90 days. Regardless of the exact duration, the principle remains: parchment acts as a protective layer, allowing the beans’ cell structure to stabilize, prolonging shelf life and preserving flavor. Ventilation in storage was another missing element—without it, coffee cannot “breathe,” which may diminish quality over time.

Roasting presented its own set of challenges. Hacienda Pomarrosa relied on an 8-pound Sivetz fluid bed roaster, affectionately dubbed the “kindergarten roaster.” While functional, it lacked the consistency and control required to develop precise roast profiles. To address this, I sought assistance from my network. Thanks to Roukiat Delrue, a Q grader and World Barista Championship head judge in Guatemala, I connected with Alfredo Rodriguez, a local Q instructor. On October 26, 2014, Sebastian and I traveled to Hacienda Ponce to conduct sample roasting.

We focused on developing roast profiles for pulp-natural coffees from the previous year’s harvest. The samples were sent to Roukiat for evaluation. Her feedback was constructive: Pomarrosa’s coffee exhibited dry fruit notes, the roast was adequate, but the overall complexity was lacking. The coffee was mellow—not spectacular, but not poor either. This assessment reaffirmed my belief that careful experimentation—focusing on ripeness, precise processing, and meticulous selection—could significantly elevate the quality of Hacienda Pomarrosa’s coffee and position it as a contender in the specialty market.

Pea-Berries, Precision, and the Quest for the Perfect Cup

Beyond separating defects and broken beans from the green coffee, I took the initiative to sort pea-berries, a unique and often overlooked anomaly. Pea-berries form when a raindrop or strong wind knocks over a coffee flower’s pistil, causing only a single bean to develop instead of two. This lone bean absorbs all the sugars and amino acids that would normally be shared, creating an unusual flavor profile.

During roasting sessions with Alfredo Rodriguez, we separated pea-berries from the larger beans to evaluate their potential. Upon cupping, Alfredo scored the pea-berries between 83.5 and 85, while the larger beans scored 84.5 to 86 as they cooled. From my perspective, the larger beans held more promise; the pea-berries seemed too watery and lacked body, suggesting a need for more careful roasting to bring out their sweetness. Yet this highlighted a key challenge: cupping is not always an accurate indicator of final cup quality. As Geoff Watts, green buyer for Intelligentsia Coffee, notes in The Myth of the Golden Tongue: “Any taster worth his/her salt will acknowledge that the human sensory system is an imperfect instrument. On top of this, coffee is also one of the most chemically complicated beverages known to mankind, making it hard stuff to measure.”

Sometimes, local coffees weren’t enough. I craved complexity, vibrancy—African coffees. A friend and roaster, Alessio Troia from New York, generously sent me samples from various regions, keeping my palate inspired and engaged. His support was invaluable during my time in Puerto Rico.

I also brought my own brewing equipment: a Hario V60, Aeropress, and Ibrik, the latter a gift from Stavros Lamprinidis, World Ibrik Champion of 2014. My goal was to master the art of Ibrik brewing using recipes from Stavros himself. On October 31, 2014, I spent hours experimenting with Hachira Ethiopia coffees, striving for the perfect cup. Brewing with an Ibrik requires patience and precision: the crema must rise flawlessly, and timing is everything to know when the coffee is ready to remove from the heat. Each attempt taught me more about the subtle art of extraction, patience, and understanding coffee beyond mere tasting—a lesson in devotion to craft that no cupping table could fully convey.

Ibrik, Inspiration, and the People of Hacienda Pomarrosa

I was far from an expert in Ibrik brewing, but over time, I began making real progress. One coffee that marked a breakthrough for me was Ethiopia Adado, roasted by Alessio Troia. When I finally felt I had nailed the technique, the cup revealed an incredible, thick mouthfeel—rounded, layered, and long-lasting. Flavors unfolded beautifully, with notes of grapes, raspberry, butterscotch, and a subtle cognac finish. It was then that I truly began to appreciate the Ibrik: it demands effort, the right coffee, and meticulous preparation, but rewards with a complexity unlike any other.

At the sorting table, I also encountered the heart of Hacienda Pomarrosa: its people. Among the ladies selecting coffee cherries, I met Ursula, an 86-year-old matriarch who worked alongside her daughter and grandson. Despite her age, she was vibrant, standing long hours, sociable, and quick with a smile or a laugh—even when my Spanish wasn’t perfect. Ursula often brought treats and coffee to share with everyone, demonstrating a warmth and generosity that made the farm feel like home. When I asked her whether she preferred life in the past or present, she smiled wistfully and said she cherished the old times more.

The farm itself captivated me as much as its people. The lush flora, the quietude, the serene rhythms of the land—it was the escape I had longed for after years in Los Angeles. I had needed to step away from the city, its endless stress, long working hours, and ceaseless noise. Hacienda Pomarrosa offered the perfect environment to immerse myself in nature, to understand the biology of coffee, and to share these experiences with the world via social media.

While planning my trip, I also kept an eye on the upcoming Puerto Rico Barista Championship, scheduled for November 8, 2014. Having previously served as a technical judge at the Big Western Regional Competition in Los Angeles and as a visual judge at the first U.S. Latte Art Championship in Seattle, I wanted to expand my judging experience toward qualifying as a World of Coffee event judge. After corresponding with the event organizer, Lucemy Velasquez, I was invited to participate in the judges’ calibration. The challenge? The session would be conducted entirely in Spanish. I understood the stakes: these were seasoned local judges, and while the language barrier added pressure, I was determined not to give up.

Judging, Friends, and Coffee Mentors in Puerto Rico

I was eager to step into my role as a judge at the Puerto Rico Barista Championship. Since Hacienda Pomarrosa was two hours from the city, it was impractical for the farm to drive me back and forth over the two-day event. I booked a hotel closer to the competition, the Country Club Inn in Cidra, and prepared for the experience ahead.

One particularly exciting aspect was the presence of Francesco Sanapo, Italian Barista Champion, sixth-place winner at the 2013 World Barista Championship, owner of Florence’s specialty coffee shop Ditta Artigianale, and organizer of the reality show Barista and Farmer. Meeting Francesco and discussing coffee with him had long been a dream.

During the calibration, I was thrilled to reconnect with friends I had met through Facebook, Jose Garcia and Javier Ar, both passionate about coffee and dedicated to teaching and coaching others locally. I also had the opportunity to meet Rebecca Atienza, producer of Hacienda San Pedro and current president of Barista and Farmer in collaboration with Francesco Sanapo. It was there I met Pedro Trila, owner of the specialty coffee shop Coffea, former Puerto Rico Barista Champion (2003, 2005, 2006), and representative at WBC in Seattle (2005) and Bern, Switzerland (2006). Pedro is a passionate mentor, guiding young baristas in their pursuit of specialty coffee careers. Alongside him, his Swedish-born wife, Janina, also served as a barista competition judge.

Judging a barista competition is both rewarding and challenging. Fairness is critical, and competitors are encouraged to fully understand the rules and regulations to avoid penalties. Competitors are evaluated by four sensory judges, two technical judges, and one head judge overseeing the process. Judges assess presentations according to WBC standards, adhering to rules, score sheet protocols, and core values, ensuring consistent and accurate scoring.

As a technical judge, my responsibilities included monitoring baristas’ compliance with technical standards, ensuring they operated the espresso machine and grinder correctly, maintained organized workspaces, upheld hygiene standards throughout their presentation, and maintained smooth workflow from start to finish. The role required both focus and fairness, but the satisfaction of witnessing the artistry and skill of each competitor made every moment worthwhile.

Lessons from Competition and Rainy Harvests

During my judging of the Coffee in Good Spirits category, one competitor inadvertently broke a key rule: he had pre-ground his coffee for a French Press prior to the competition. In such cases, the barista either failed to read the rules or ignored them entirely, which directly impacts the professionalism score. Coffee is an extraordinarily delicate product; once ground, it quickly loses its aroma, and the volatile compounds responsible for its flavor begin to dissipate. Pre-grinding results in a beverage that often tastes flat or dull, masking the unique terroir that the barista intended to highlight.

When I explained my scoring decision to the competitor, he claimed he hadn’t seen that rule. While the competition proceeded smoothly overall, there were minor technical issues that highlighted areas in need of improvement, especially if Puerto Rico aims to align its events with world standards. One notable challenge was language flexibility: judges whose first language was not Spanish struggled at times, and the head judge, despite knowing English, interacted with me primarily in Spanish, which I found unnecessarily rigid. Fortunately, my Spanish skills were sufficient to understand most of the questions, and I was able to complete the calibration and judge as a technical judge in the Campeonato Nacional de Barista de Puerto Rico, an achievement I had been eager to accomplish.

After the competition, I returned to Hacienda Pomarrosa to continue experimenting with three processing methods: Honey (pulp-natural), Ethiopia washed, and Burundi dry, all aimed at elevating the coffee’s quality. On November 15, 2014, it rained steadily, but that did not deter me from harvesting cherries for the Burundi dry process. I got drenched twice, returned to the house to change, and went back into the fields, determined to collect enough coffee to meet my goals.

A recurring point of contention at the farm was Sebastian’s reluctance to use the full harvest I had carefully sorted. I aimed to combine my meticulously selected red cherries with other harvests of similar quality for the pulp-natural process, but convincing him of the benefits of selective blending remained a challenge. Despite these obstacles, the pursuit of quality continued, one cherry at a time.

Taking Risks—Experimenting Beyond Tradition

Implementing new processing methods at Hacienda Pomarrosa was far from straightforward. Using a manual de-pulper, cherries were immediately placed into the mechanical dryer, where water content was not an issue. Yet Sebastian, the farm manager, lacked confidence in the alternative methods I introduced.

The pulp-natural process, for example, produces a coffee that is sweet, flavorful, and often carries delicate acidity. But I thrive on experimentation—taking risks is essential to progress. As Michaele Weissman wrote in God in a Cup: “The truth is, most human beings resist change more vigorously than those whose lives are steeped in local tradition.” I understood that experimenting with washed Ethiopia and dry Burundi processes could fail; they might even compromise the hard work already invested. Yet there was no turning back. I remained determined, optimistic, and committed to exploring what Puerto Rican coffee could achieve.

I drew inspiration from producers like Aida Battle from El Salvador, who also experimented with African processing methods. For her, it did not take just one harvest to see results; it required patience, careful observation, and consistent application of knowledge. Applying Ethiopian or Burundian processing techniques to the high-altitude climate of El Salvador—or Puerto Rico—requires more than method; it requires adaptability and insight to unlock flavors that challenge expectations. The goal is to create coffees that make people say: “I’ve never tasted anything like this before.” The battle for innovation continued.

The farm’s main varietals—Typica, Red Caturra, and Sarchimor—each present unique challenges and opportunities. Caturra, a Brazilian cultivar discovered near the town of Caturra in the 1930s, is a high-yielding mutation of Bourbon. Its dwarf stature makes it shorter than Typica or Bourbon, with a thick base and varying numbers of secondary branches. Interestingly, not all Caturra trees are identical; some have large leaves, others medium. Red Caturra dominates the farm, with a few yellow Caturra interspersed.

When properly processed and dried, island coffees like these can carry remarkable acidity, brightness, and complexity, defying the perception that Puerto Rican coffee is mild or uninteresting. The potential is there—it only requires the willingness to innovate, experiment, and take risks beyond tradition.

Experimenting with Altitude, Soil, and Grading

Low elevation in coffee-growing regions tends to reduce acidity, but it does not eliminate it entirely. Soil composition, fertilization, sunlight, and rainfall all play critical roles in developing a coffee’s flavor profile. At Hacienda Pomarrosa, the main varietals included Typica, known for its conical shape, tall vertical trunk, and secondary branches. When properly harvested and processed, Typica delivers a sweet, clean acidity reminiscent of its origins in the Kaffa region of Ethiopia.

One of my key suggestions to the farm was to invest in a grading and sorting machine. Such equipment could separate broken, defective, and small “pea” beans from the rest, ensuring a cleaner, more uniform crop. Unfortunately, the farm owner showed little interest in these investments, focusing instead on a machine capable of separating red and ripe cherries from green and yellow ones. Alfredo Rodriguez, a local Q instructor and roaster, had similar grading machines at his farm. He generously allowed us to bring 400 pounds of the previous year’s crop to test them. While the machines were not perfect—they could not fully remove all defects or pea-berries—they dramatically reduced the workload for manual sorting.

On December 2, 2014, I was ready for the next harvest to start my experimental processes, but most of what the pickers brought in was Sarchimor. I had no choice but to process Sarchimor separately using the pulp-natural method to evaluate its ripeness and flavor potential. By December 4, I concluded my final harvest, which I proudly called Mission Completed. The next step was careful drying and allowing the beans sufficient resting time before hulling.

Excitement and nervous anticipation filled me as I thought of Rubens Gardelli, the 2nd place winner of the World Brewers Cup 2014 in Rimini, Italy. On October 30, 2014, Rubens sent a message that fueled my motivation:

“Dear Mikhail, I admire your passion and dedication for coffee quality. It’s such a great joy watching your posts on Facebook. As you might know, I competed for the World Brewers Cup and placed 2nd. Next year I will try to win again in Italy and I am in the coffee selection phase. My question is simple: is there a possibility to taste a sample of the very best lot you have harvested and processed? Keep on doing what you’re doing—it’s delightful.”

The challenge was timing. Coffee ideally needs 60 to 90 days of resting in parchment before milling to stabilize flavor, and by early November only the Honey process and Ethiopia washed coffee would have sufficient resting time. The Burundi dry process was too fresh to risk shipping. Rubens, however, was willing to experiment with super-fresh coffee. He insisted on trying all three processes to see which would perform best in competition, embracing the uncertainty and risk that I had been navigating all season.

Sending Puerto Rican Coffee to the World

I was still holding hope that the coffees I was experimenting with at Hacienda Pomarrosa would transform in cup profile, revealing the sweetness and brightness I knew they could achieve. Talking to Rubens Gardelli made me feel reassured—finally, someone who was as much of a coffee geek as I am.

Sending him the coffee was a fully transparent process. He knew exactly which farm each coffee came from. This transparency, which I also maintained through social media for coffee professionals, included details about my processing methods, the altitude where the coffee was grown, and the environmental practices applied on the farm. Transparency, in my view, is a way to reward the farmers for their hard work and investment.

I was aware Rubens had other coffees to evaluate for the competition, and he conducted blind cuppings, letting the highest-scoring coffee determine what went to the stage. Island coffees, like those from Puerto Rico, are always tricky in competition. Most baristas today chase high acidity and sweetness, often favoring Ethiopian, Kenyan, or Geisha varieties. Many hesitate to use alternative coffees for fear of losing. For me, the philosophy is simple: if you love your coffee and can describe it accurately, your presentation can score highly regardless of the variety. I hoped one day baristas would have the courage to compete with something other than Geisha.

In January, Rubens received the coffees I had shipped. He roasted them himself and cupped each lot. Among the three processes I had worked on, he singled out the Burundi Dry process and the Honey process as exceptional. Yet, for the competition, he chose a different coffee: El Salvador Manzano, Red Bourbon, natural process. He shared his feedback with me:

“Just tried the Burundi Dry process in espresso, 30 minutes after resting. It is super smooth and super sweet. I liked it a lot. I expected less acidity, but you did a great job. The Ethiopia washed process has a high level of acidity; for the Honey process I expected less, but it is there. Honey process is much better, in my opinion, than Ethiopia washed process. The Ethiopia washed has a longer aftertaste but slightly astringent. Burundi Dry process is amazing. Overall, all these coffees are high in body, high in acidity, and super sweet. Believe me, you have obtained the best from those beans. Your coffees are very good, and I love them in espresso.”

Hearing this from Rubens was exhilarating—I hadn’t yet had the chance to cup or taste these coffees myself. The plan was to schedule a cupping and tasting on January 17, 2015, at the University of Puerto Rico, Utuado Campus, at the Specialty Coffee Institute of the Caribbean. The news from Italy gave me a surge of confidence. I now believed fully in my work and knew that I could extract unique dimensions from Puerto Rican coffees, and that my experiments had paid off.

As for the processing at Hacienda Pomarrosa, certain practices had evolved since my arrival, yet ultimately, it was the farm’s decision whether to embrace the specialty market methods or revert to traditional practices. The choices they made would determine whether Puerto Rican coffees could truly shine on the global stage.

Experimenting with Fermentation – Ethiopia Washed and Burundi Dry

At Hacienda Pomarrosa, I was taking risks, experimenting with processing methods to push the boundaries of what Puerto Rican coffee could offer. The dry and fermentation processes I implemented were designed to bring out the fullest expression of the island’s terroir. We all know that the mucilage surrounding coffee beans—rich in natural sugars and alcohol—plays a crucial role in developing acidity, sweetness, and flavor. By carefully manipulating how mucilage is handled, I could influence the final cup, highlighting the unique character of Puerto Rican coffee.

Sugar and alcohol in mucilage break down during fermentation, aided by bacteria and microbes, which is critical for clarity and flavor development in the coffee bean. For these experiments, my goal was not only to enhance sweetness and acidity but also to reveal the nuanced flavors that the island’s terroir could offer.

Ethiopia Washed Process

I approached the Ethiopia washed process unorthodoxly, which likely made it less popular among coffee professionals at first. I started with a primary fermentation of 48 hours, submerging the beans in water. Every 12 hours, I discarded the old water, washed the beans thoroughly, and added fresh clean water. Following this, a secondary underwater fermentation extended for another 48 hours instead of the conventional 24, allowing the beans to sit fully submerged in clean water. This step aimed to emphasize acidity while maintaining sweetness.

After the double fermentation, I meticulously washed the beans by hand, ensuring all remaining mucilage and bacteria were removed. The beans were then dried in a mechanical dryer until they reached a target moisture of 10–12%, before resting in parchment in the warehouse to stabilize.

Burundi Dry Process

The Burundi Dry process was a hybrid between honey and washed methods. I began with 24 hours of dry fermentation, keeping the mucilage intact while the beans rested. After manual de-pulping, the beans were washed every 12 hours without removing all the mucilage. Following this, they underwent another 24 hours of underwater fermentation, after which I performed a final meticulous wash to remove floaters and ensure cleanliness.

During the first 24 hours, the mucilage clung to the beans, allowing them to absorb sweetness and begin developing acidity. It was only in the underwater fermentation that the mucilage was fully removed. Afterward, the beans were dried on the mechanical dryer until reaching the proper moisture content, ready to rest in parchment.

Cupping and Evaluation

To assess the results, I organized a cupping session on January 17 at the University of Puerto Rico, Utuado Campus, at the Specialty Coffee Institute of the Caribbean. Local Q graders and specialty coffee baristas were invited to taste and evaluate 11 different coffees, including those from my Ethiopia washed and Burundi dry experiments. The session provided an opportunity to see firsthand whether these experimental methods had truly elevated Puerto Rican coffee to new levels of sweetness, acidity, and flavor complexity.

The first round of cupping immediately revealed the spectrum of coffee quality. Some cups contained robusta, instantly recognizable by their small bean size. Contrary to popular belief, the defining characteristic wasn’t excessive bitterness but an unpleasant metallic or rubbery note. Another cup showed signs of over-fermentation, tasting baggy and medicinal, while several others were dry, lacking both sweetness and brightness.

The cup that caught my attention was one I had processed myself using the Honey method. It offered moderate sweetness, mellow acidity, and notes of dried fruit, with a black tea-like texture. Its light body and pleasant aftertaste made it stand out. All cupping was conducted blindly, with no knowledge of the farm origin, which made this recognition even more satisfying.

The second round brought coffees that were more inconsistent. Some lacked sweetness and acidity, while a natural process cup had over-fermented, tasting of rotten blueberries. Another poorly fermented coffee presented a sharp, vinegary sourness, reminiscent of expired milk or yogurt. Yet among these challenging cups, two stood out.

The first, my Burundi Dry process, delivered a perfect balance of sweetness and elegant acidity, with a silky mouthfeel and a sparkling texture. Subtle notes of watermelon, sweet tobacco, and hibiscus cold brew tea rounded out the complexity, making it one of my favorites of the day.

The second standout, the Ethiopia washed process, had a high level of citric acidity but lacked sweetness, likely due to a misstep in fermentation. Originally intended for 24 hours of underwater fermentation, I had accidentally extended it to 48 hours, which enhanced acidity but compromised sweetness. Despite this, the cup still showcased potential, and I knew a future adjustment could bring balance.

This experience solidified my belief in the importance of using fully ripe cherries and precise processing to achieve distinctive, high-quality cups. The Burundi Dry process, in particular, revealed inherent sweetness and multi-dimensional flavors, even from coffee grown at lower elevation. As the Specialty Coffee Association of America (SCAA) notes, sweetness is the perception of certain carbohydrates that create a pleasing fullness of flavor—a quality the Burundi Dry process captured beautifully.

My vision for Hacienda Pomarrosa is clear: continue refining the Burundi Dry and Honey processes while revisiting the Ethiopia washed method to enhance sweetness without compromising acidity. By embracing the unique terroir, soil, and climate of Puerto Rico, we can transform one-dimensional cups into complex, multi-layered experiences, challenging the stereotype of local coffee as dull or flat.

As Geoff Watts of Intelligentsia reminds us, “Unilateralism or difference to one tongue at the cupping table causes blindness. Overconfidence can easily stifle a cup per’s accuracy, and we’ve got to remember that we are still students… and always be.” And as James Hoffman of Square Mile Coffee adds, “I still believe that creation of quality ends the moment you pick a coffee, and that every single step afterwards is about preservation and transparency.”

Through careful experimentation and unwavering dedication, Puerto Rican coffee is capable of achieving sweetness, brightness, and complexity, even at lower elevations—proof that quality is a choice, not a limitation.

Article by Mikhail Sebastian Okunuga

First was published as an educational book on February 04, 2015